By creating the first global network of networks, we made the Internet a functional, worldwide commercial system that enabled the most transformative event in human history: the globalization of eCommerce.

Visionaries and engineers of packet switching, internetworking, and web applications built the original foundations for the Internet. Our contribution was turning those innovations into a working worldwide utility.

Beginning in 1996, we connected the world’s major ISPs and enabled ≈95 percent of Internet users to communicate on a single, uninterrupted network with round-trip latency under one-third of a second. For the first time, this performance was delivered globally and securely, including end-to-end SSL connections. This is the moment the Internet moved from invention to industrialization and became a functioning worldwide system.

As our network came online in each major market, we turned the Internet into a seamless worldwide communications portal, shopping mall, and secure financial platform.

In my book, How I Made the Web World Wide, I chronicle my journey as co-founder of Digital Island in 1996. This pioneering Internet infrastructure company transformed the Internet from a collection of fragmented regional ISPs into the world’s first unified Tier-0 global network of networks, the literal definition of “the Internet.”

Key Achievements of Our Network

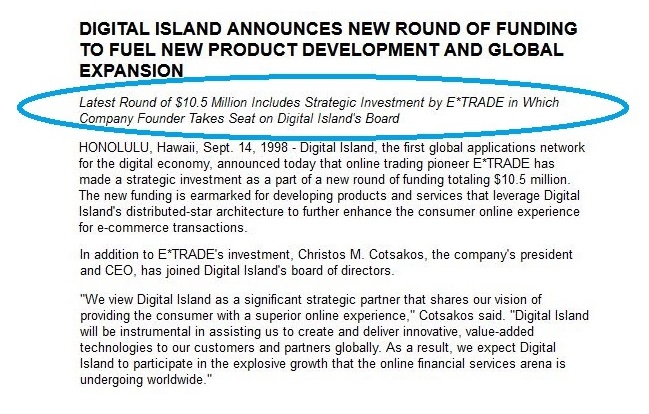

- Enabled the globalization of eCommerce with Visa, MasterCard, Charles Schwab, and E*Trade.

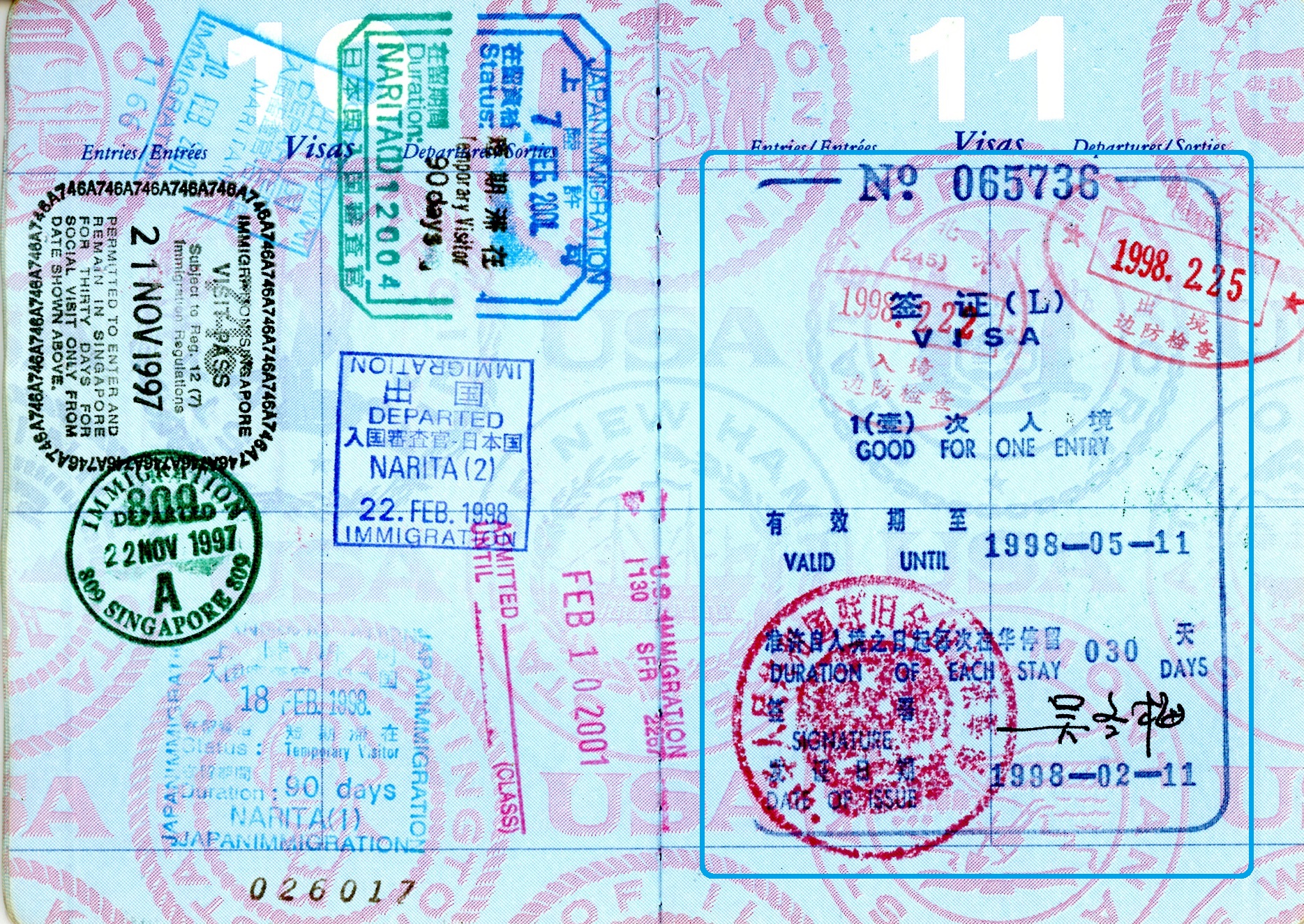

- Enabled the first Internet peering connectivity with the People’s Republic of China, which I contracted during my travels to Beijing while negotiating terms of service with the Minister of Telecom, Professor Xing Li of Tsinghua University.

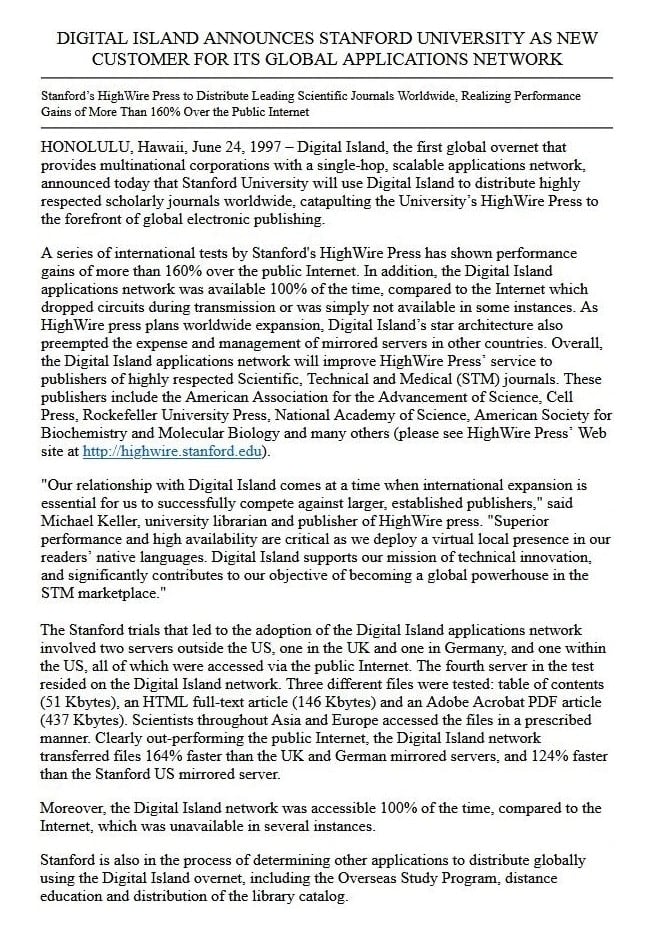

- Enabled eLearning and ePublishing with Stanford University.

- Enabled the world’s largest media streaming network, built in partnership with Microsoft, Intel, and Compaq.

- Enabled the first global Content Delivery Network (CDN), two years before Akamai was founded in 1998.

- Enabled the first Network-as-a-Service (NaaS) implementation for on-demand bandwidth allocation over the Internet, using the Reservation Resource Protocol (RSVP).

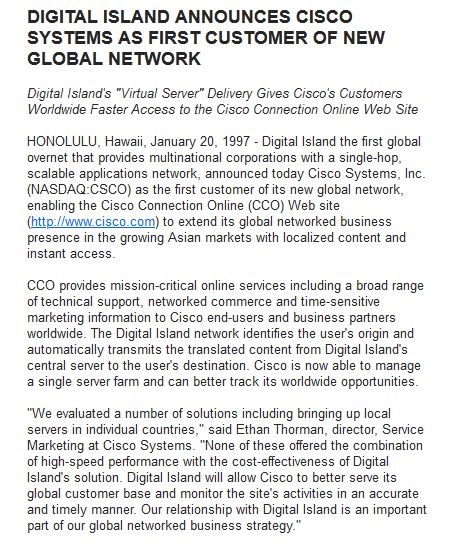

- In 1996, when I negotiated and signed the service contract with Cisco Systems to host Cisco.com, Cisco ranked as the 587th largest company in the United States. Three years later, they became the most valuable company in the world while relying on our network to scale their growth.

- The award and recognition as the world’s first Cisco Powered Network, which became the global internetworking industry benchmark.

- This netword was the de facto Internet access platform used by Google’s founders in 1998 to build the first repository of search results while they were graduate students at Stanford University (google.stanford.edu), supported by our role as Stanford’s ISP beginning in Q1 1997.

- Creating Traceware, a patented algorithm developed with Stanford University’s HighWire Press. This technology uses real-time data processing to automate regulatory compliance for global media, addressing both regional and localized requirements.

The eCommerce Crossing of the Rubicon

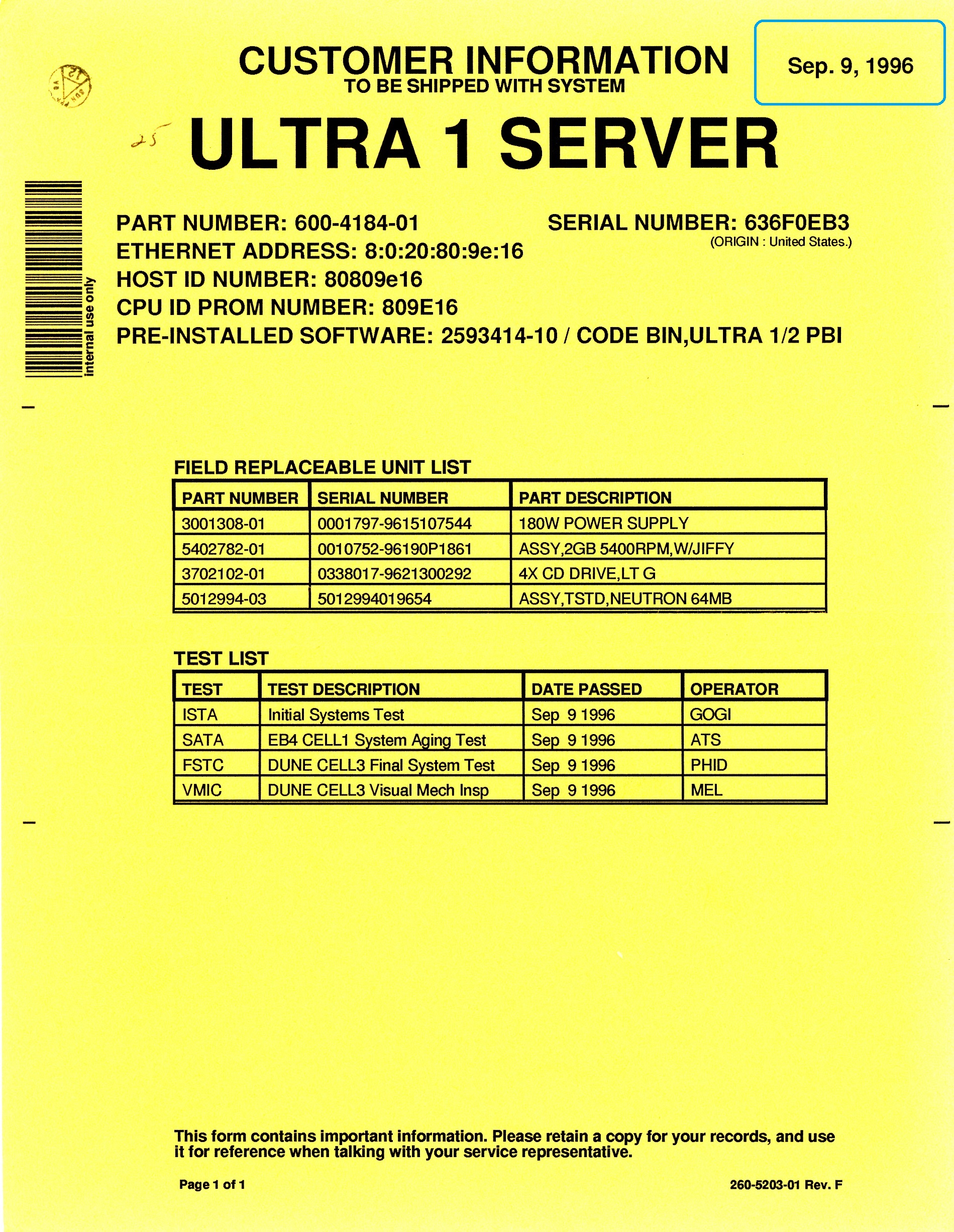

Starting with a bold vision, between 1996 and 1999 our team raised $779 million to build a global telecommunications network of networks that reshaped worldwide connectivity. Our shareholders, investors, and customers included ComVentures, Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs, Chase Capital, Cisco Systems, Stanford University, AOL, Sun Microsystems with 5,000 dedicated servers, Visa, MasterCard, Charles Schwab, and E*TRADE.

The market validated this platform not only through network adoption, but also through capital and strategic partnership. In addition to our earlier venture rounds, in June of 2000 Digital Island completed a $45 million private equity investment led by Microsoft, Intel, and Compaq with 8,000 dedicated servers. This was a four-way validation signal that the world’s largest software, semiconductor, and computer companies recognized Digital Island as the emerging global Internet operations layer.

Deploying tens of thousands of dedicated servers worldwide was not a software design. This was real world hardware, money, multi-billion dollar companies, and eCommerce in play. It required global logistics, redundant and diverse physical facilities, power, cooling, and nonstop operations at a scale of an industrial manufacturer, and not the controlled lab room of a University proof of concept project.

The investors and strategic partners were not passive spectators. They supplied the capital, infrastructure, and institutional trust required to globalize the Internet and ignite a worldwide financial revolution.

The Vision and Solution

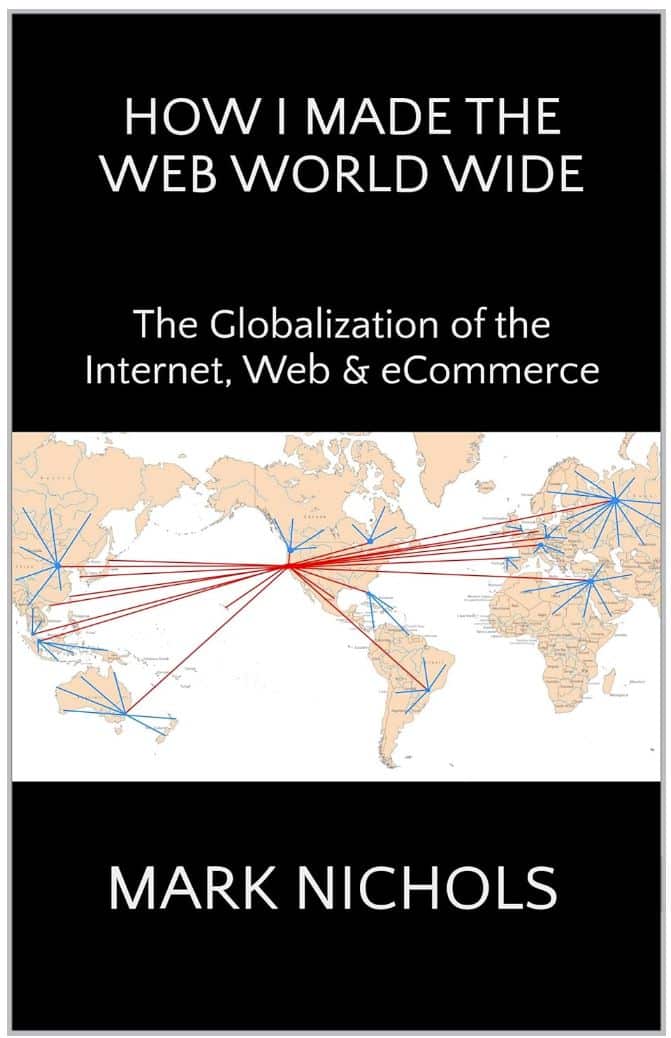

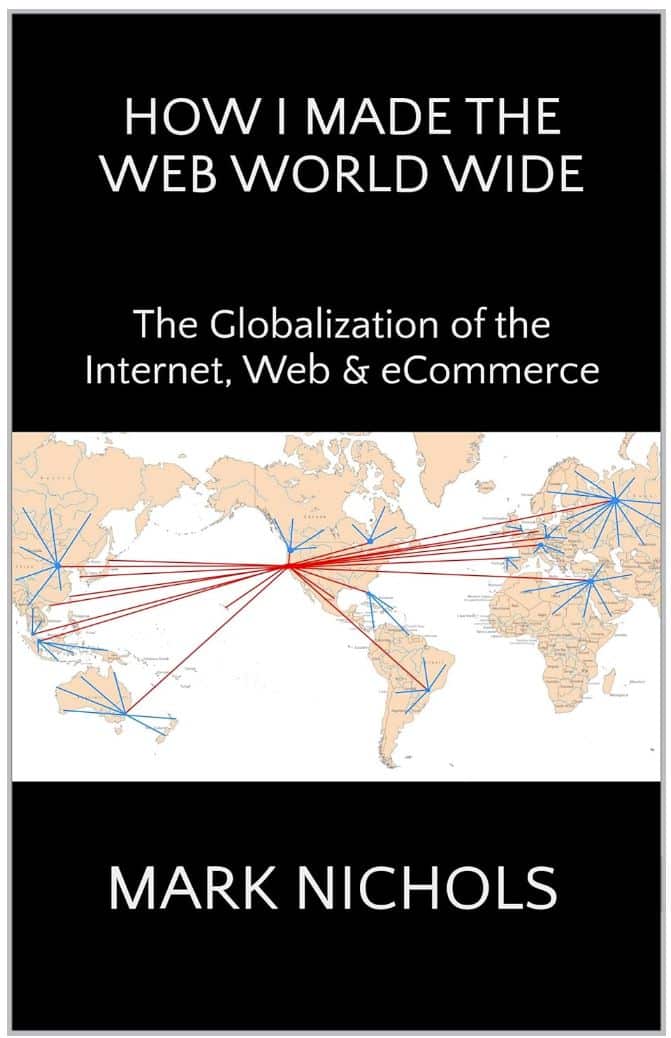

Envision 1996 and consider the illustration below, where the blue lines represent the service areas of regional Internet providers such as France Telecom, Japan Telecom, Singapore Telecom, and Deutsche Telekom. The red lines depict the oceanic and terrestrial fiber optic IPLCs that I contracted for and put into service, linking every major metro with an Internet presence around the world.

This is the story of How I Made the Web World Wide.

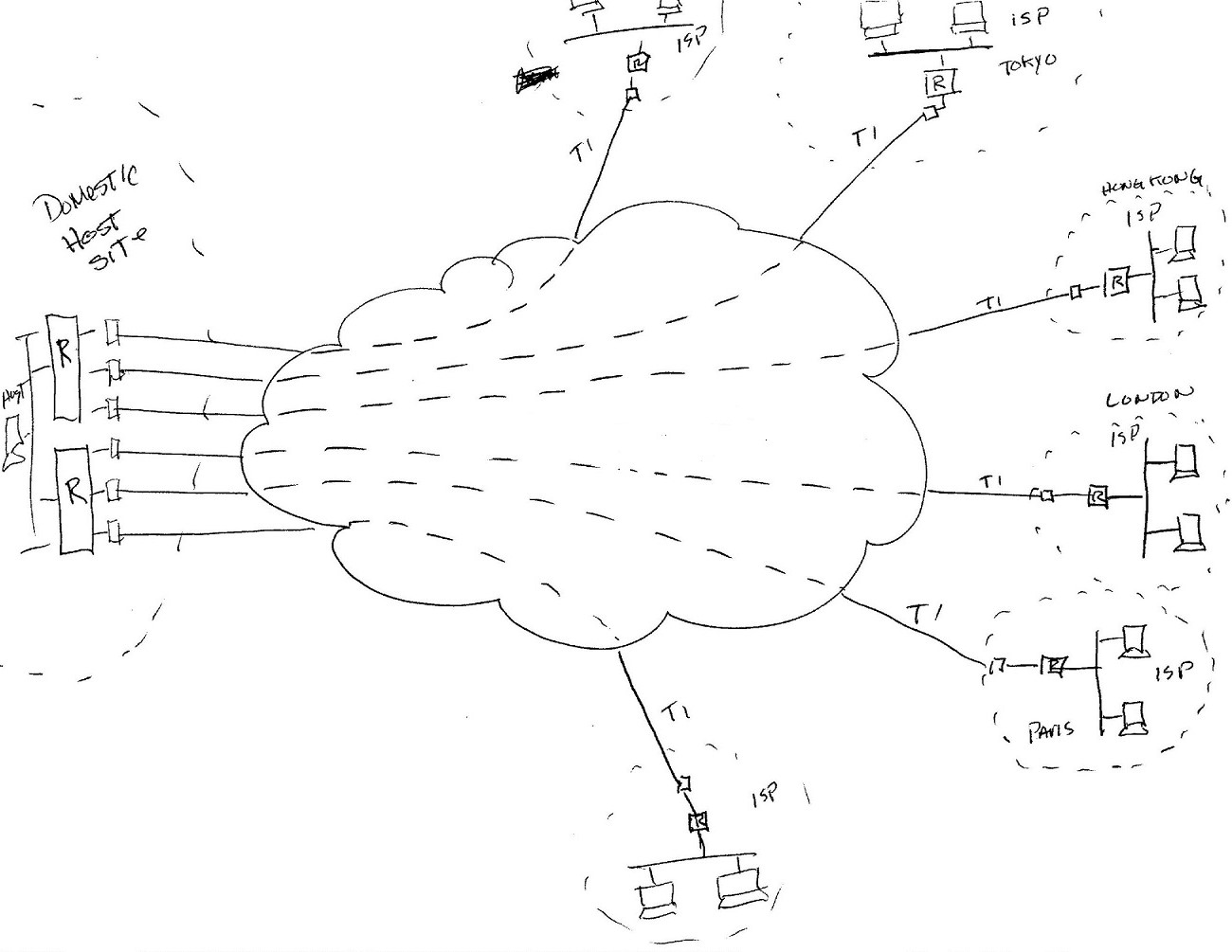

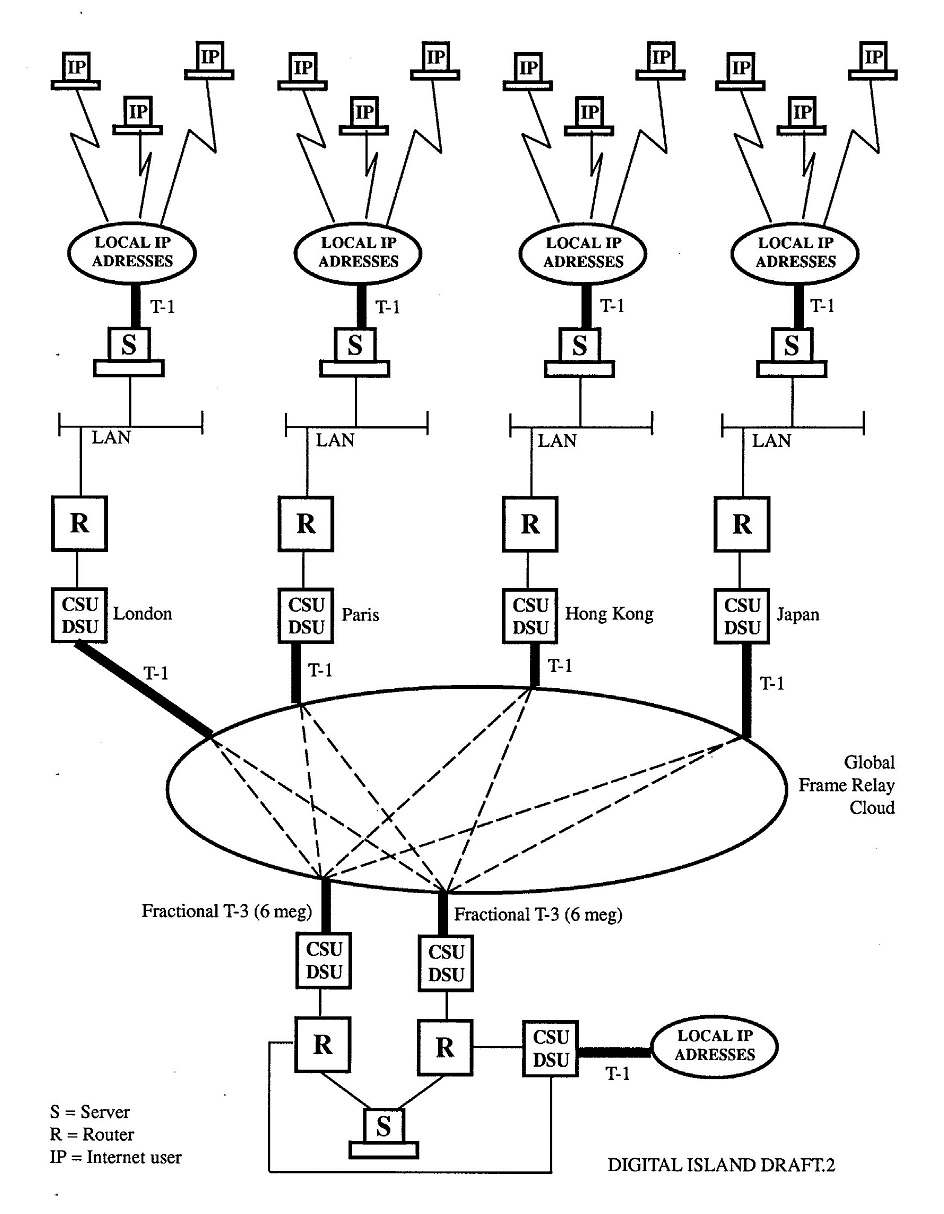

The Genesis Network Diagram and the Two Foundational Pivots to Globalization and eCommerce

In June 1996, I sketched the first blueprint for a network designed to globalize the Internet. It mapped planned Points of Presence for a global wide-area network spanning Asia-Pacific, the Americas, and Western Europe, with additional placeholders for the rest of the world.

This hand-drawn rendering predates our Hawaii business filing by four months. I created it while I was still employed at Sprint, roughly 60 days before I joined Ron and Sanne Higgins to launch the startup.

Pivot 1: From PacRim to Global

For the Founding Team Record: Previously to CoFounding Digital Island, Ron Higgins was a Director of Sales at Radius Inc., a computer hardware firm, and Sanne Higgins was from media communications; neither had telecom or commercial real estate background – those were the roles I performed.

Pivot 1: From Pacific Rim only to Global

When I first met Ron, his original concept was to create a Digital Publishing Service in the Pacific Rim. After I did some networking due diligence, I pushed the concept from a regional idea to a global build after noting that the initial plan to use the telecom services of frame relay would cost the same whether we connected within Asia (Tokyo, Taipei, Seoul), or we included Europe, Latin America, and res of world (Paris, Frankfurt, São Paulo).

After I explained to Ron that there was no financial benefit to the Pacific Rim only regions, Ron understood and agreed that we would pivot to a global translation concept. As the diagram above represents, supporting translation of English-language sites now into a global opportunity.

Note: Ron was under an impression that Hawaii to Asia was cheaper and benefited from less latency than Pacific Rim circuits originating from California. This was an error of judgment that I corrected. There is more detail about this sensitive subject matter towards the “Additional Reading” section at the end of the website, and in the Chapter 3 of my book.

Pivot 2: From Digital Publishing to eCommerce

Four months later, the plan changed again. What began as translation and digital publishing became a plan to enable global eCommerce. We moved beyond frame relay and committed to International Private Line Circuits, which enabled guaranteed latency, reliability, and quality of service.

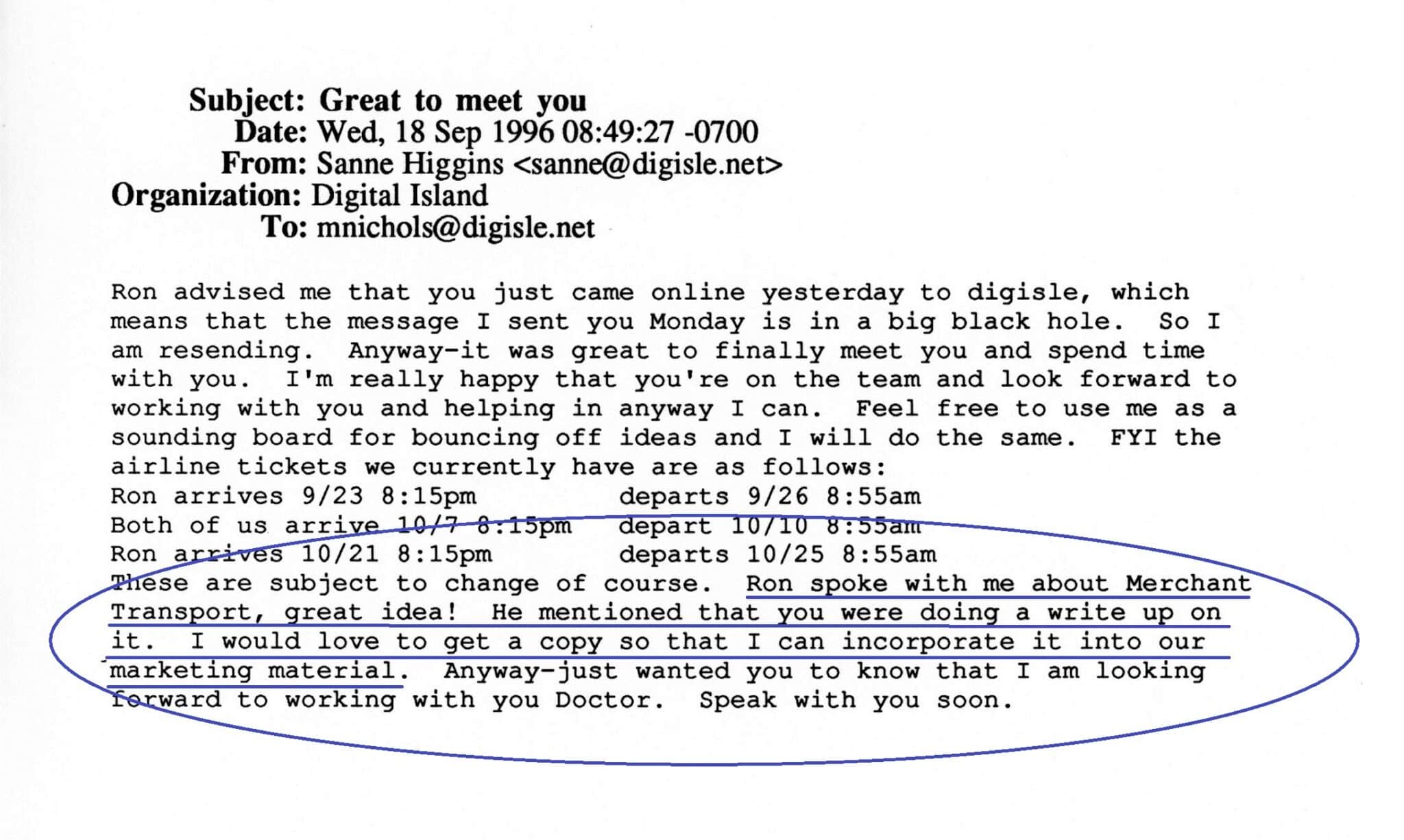

This pivot is evidenced in the September 18, 1996 email from Sanne Higgins, sent after Ron discussed my Merchant Transport concept with her. She called it a great idea and requested my write-up to incorporate into marketing materials.

As of September 6, 1996, Ron was still positioning the proposed business as a Pacific Rim-centric hosting and translation services company. Within twelve days of the Hawaii registration, the business model changed significantly after I suggested the opportunity for Merchant Transport and eCommerce. This shift set the stage for the globalization of Internet-based financial services.

The Birth of the Globalization of eCommerce

During my visit to Hawaii with Ron and Sanne in the second week of September 1996, we expanded the network design, budget, and operational complexity required to build and manage our own network. The new goal was enabling Merchant Transport and the globalization of eCommerce.

Within six months of that pivot, we onboarded Visa International as our third customer, following Cisco Systems and Stanford University as the first and second clients. Soon after, E*TRADE, Charles Schwab, and MasterCard joined the network.

What It Took to Make the Internet Global

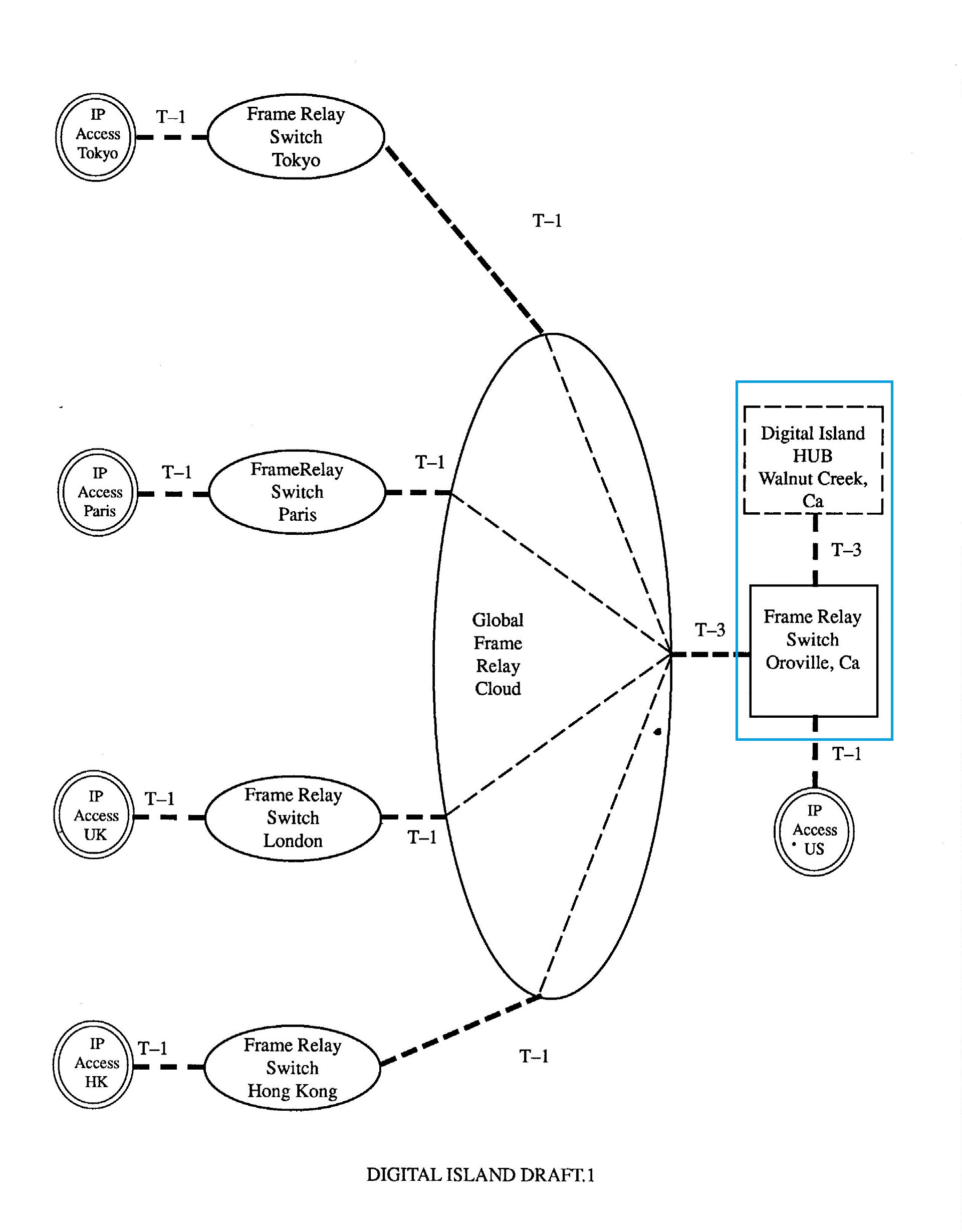

In July 1996, I drafted the network diagram shown below on my Mac IIcx using Aldus PageMaker 4.0, which I had purchased in 1990. In that illustration, I identified the need to move our proposed network hub from Hawaii to California. Hawaii, the original hub choice, within the first two weeks of discussions with Ron, I learned via Sprint Engineering, that Hawaii telecom was topographically at the end of an oceanic telecom spur, was totally dependent on California, and lacked the fiber-optic access, capacity, latency, and route diversity eastbound to Asia as was required per Ron’s assumtions.

After researching and identifying these limitations, I redirected the project to California, to be in close proximity to where the Tier 1 telcos have their switching equipment.

I also realized that storing mission-critical servers on an island with six active volcanoes within a 100-mile radius was not a marketing advantage.

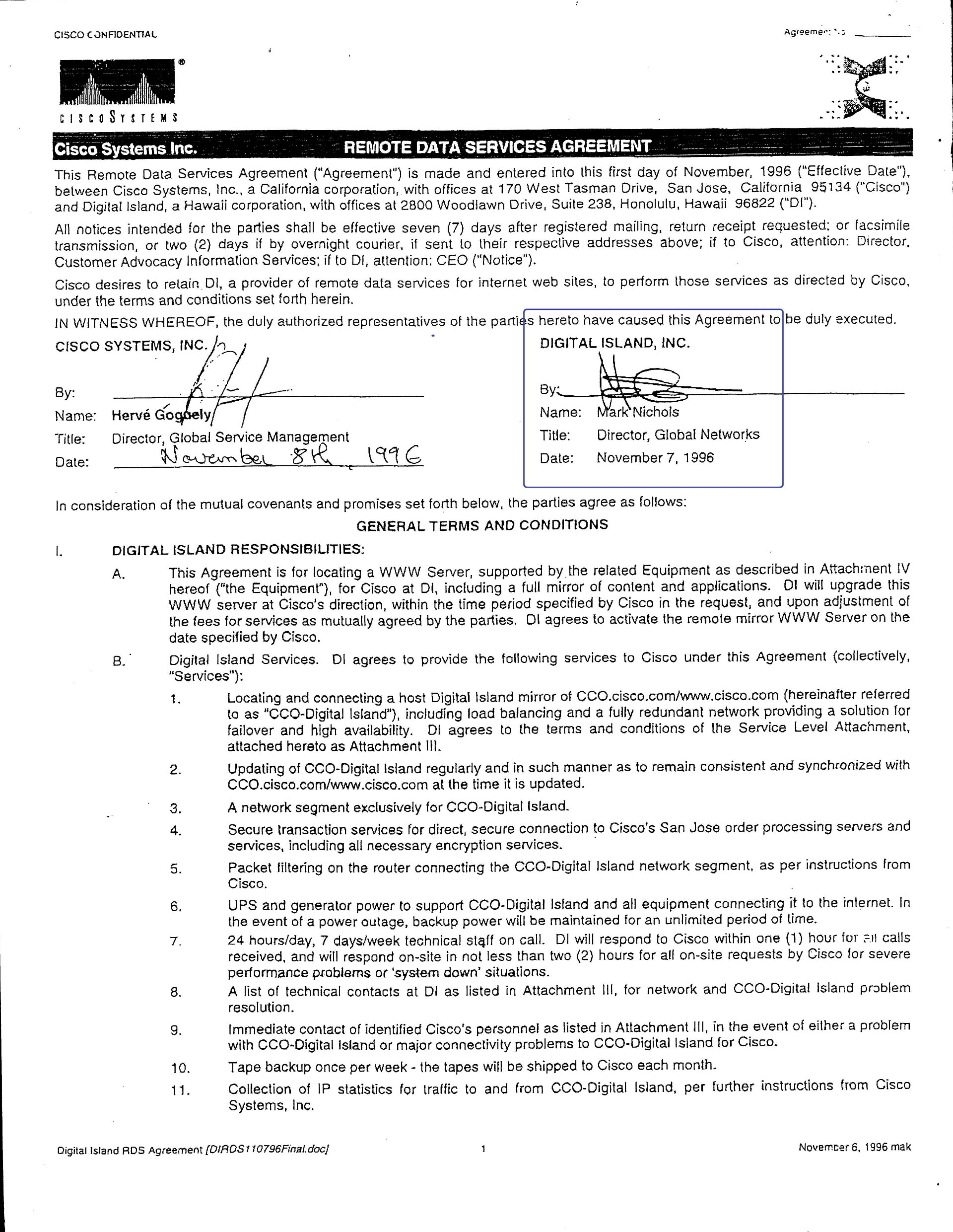

The Cisco Contract: The Commercial Inflection Point & Our Franchise Document and Meal Ticket

Without the Cisco agreement, Digital Island would not have existed anywhere outside of Fairyland

In October and November of 1996, I negotiated and executed the Cisco Systems services agreement on behalf of the Digital Island. I productuctized the services, authored the financial proforma, defined the legal text of our Quality of Service measurements and enforcements, and then endorsed the contract to bind Digital Island to the the legal terms of the contract obligations.

Note: at this moment, the Digital Island team was only Ron Higgins, Sanne Higgins, and myself. Without question, Ron and Sanne were as equally important to accomplishing what our three person team accomplished, but the terms of service of this Cisco contract is my isolated work and contribution.

After I gave the wet signature contract to Ron, he took it the same week to Cliff Higgerson of ComVentures (Sand Hill Road, Palo Alto) and secured a $300K seed investment. Ron securing the funding was as important as the contract itself.

Before the contract, the business was a concept. Afterward, it had a reference customer with defined obligations, execution risk, and revenue potential. This document gave us the lever to start implementation. And most importantly, the Cisco agreement became the inflection point that made the company financeable.

The agreement was not marketing oriented or exploratory. It specified operational service behavior that had not previously been offered as a standardized global service, including defined performance characteristics, geographic scope, and contractual accountability.

At the time of execution, no other provider had agreed to contractually guarantee comparable global behavior at that scope.

Cisco executed the agreement because it had a specific operational requirement and no alternative provider could guarantee the required behavior at global scope. The decision was commercial, not ideological.

The agreement did not validate the Hawaii hub narrative. It depended on service behavior executed through carrier demarcations and interconnection points that resided in California in less than 120 days.

The Cisco Addendum Diagram

The network illustration attached as an addendum to the Cisco services agreement reflects the evolved version of the original designs.

Our initial architecture assumed frame relay for a Pacific Rim translation and publishing service. After our Q4 1996 proof-of-concept work, we replaced that design with clear-channel circuits, International Private Line Circuits, because frame relay could not deliver enforceable Quality of Service for latency or security.

By mid-September 1996, we shifted the mission to pursue the globalization of eCommerce through secure transactional services, which I termed Merchant Transport.

The Caterpillar to Butterfly Transformation

How Did the Caterpillar Become a Butterfly?

Now visualize the following.

1) Using your imagination, remove the red lines and you see the “Internet caterpillar” of 1996

Now visualize the Internet before any global, end-to-end service existed to provide seamless access across major metros and Internet-served regions.

At that time, regional networks were disconnected. Rostelecom in Russia did not meaningfully connect to Embratel in Brazil. Malaysia Telecom did not connect to Telefónica in Spain. Korea Telecom did not connect to NetVision in Israel. And the China Educational Network based at Tsinghua University (CERNET) shared a single 64-kilobit academic intranet among hundreds of universities, with only one non-bidirectional 64 Kb link to Sprint. You can read the story of my travels to Beijing and connecting China to our network here: https://marknichols.com/china/

The timing problem was fundamental. Economies of scale required for globalization were not financially viable because no commercial model existed to produce shareholder returns on a worldwide physical presence. The software protocols existed, but the global service did not.

Without seamless global connectivity, the Internet Protocol suite, including the Web software stack, could not deliver true internetworking beyond local hosts, regional footprints, and limited peering relationships.

In practice, TCP/IP and the Web behaved like intranet tools: useful inside a company and inside a region, but not dependable as an end-to-end global utility.

We targeted that gap. Digital Island introduced a guaranteed 300-millisecond round-trip performance standard to anywhere in the world at any time. That enforceable discipline made global eCommerce viable.

2) Now with the red lines as drawn, you see the “Internet butterfly”

With the red lines in place, the Internet transformed into a coherent global platform, the infrastructure butterfly emerging from the earlier caterpillar stage.

The butterfly depended on the caterpillar stage: the protocols, early ISPs, researchers, and equipment vendors. Without the physical operational layer interconnecting them at global scale, the software remained only partially realized.

The global private lines I acquired spanned the world, creating an Internet-centric global WAN that interlinked major regional ISPs within metros and stitched regions together into a single operational system for global traffic.

By January 1999, the Digital Island network had connected the major ISPs worldwide available for Internet connectivity, including England, France, the Netherlands, Germany, Spain, Russia, Israel, Mexico, Brazil, Australia, Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Beijing, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Canada, and major U.S. metros including Miami, New York, Los Angeles, Boston, Chicago, Virginia, Seattle, Honolulu, Palo Alto, and Santa Clara.

From a historical perspective, this was a new market because global network services like ours did not exist before we built them.

We were able to contract, host, and broadcast the websites of 881 customers in under four years.

Those customers included Cisco Systems, Stanford University, Microsoft, Google, Visa, Intel, Compaq, Hewlett-Packard, E*TRADE, Charles Schwab, Novell, National Semiconductor, MasterCard, Sun Microsystems, Universal Music Group, ABN AMRO, UBS Warburg, Digital River, The Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, Reuters, MSNBC, Major League Baseball, Time Warner–Road Runner, AOL, CNBC, JPMorgan Chase, Sony, Bloomberg, and more than 850 others.

With roughly 220 business days per year, acquiring 881 customers in four years averages to one new customer per business day for four consecutive years.

The Start of $779 Million in Venture Capital and 881 Customer Acquisitions in Four Years

The financial and commercial sectors became involved in our entrepreneurial journey by supporting infrastructure investments, enabling us to convert long-available software protocols into a real worldwide commercial utility.

TCP/IP had existed for roughly twenty-two years, and the World Wide Web stack for roughly six, but neither had ever been operationalized as a single, accountable, end-to-end global network with enforceable performance and security.

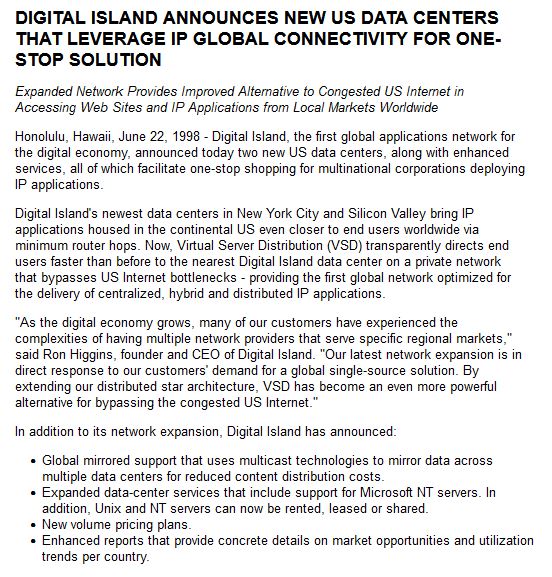

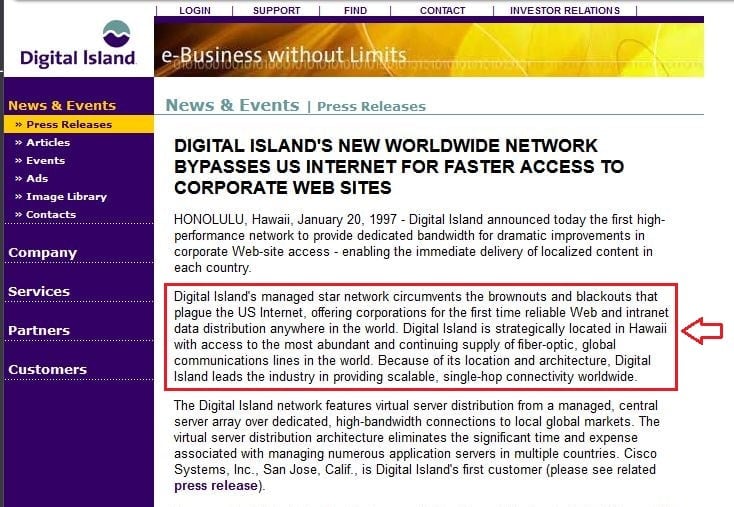

In January 1997, we issued our first press release announcing both the services contract to host Cisco.com and the debut of our new global network.

Stanford University: Our Customer, Our Partner in Patented Innovations, and Our First Silicon Valley Data Center Location

Stanford University became our second customer, supporting the distribution of their ePublication and eLearning services. Before the press release, I had already initiated our first California Point of Presence on the Stanford campus.

Stanford was one of the original ARPANET nodes in 1969, and by 1997 we were hosting and broadcasting their web presence on our global network.

Cisco and Stanford together validated the magnitude of the value proposition behind a unified global infrastructure.

Our services also provided Stanford with upstream Internet access that supported Google’s founders in 1998 while they were graduate students, including the early environment associated with google.stanford.edu.

With Cisco and Stanford on board, the technology and financial communities began to take serious notice.

E*TRADE Invests After Becoming a Customer

The acquisition of E*TRADE as a customer was followed by their investment and board involvement.

Prior to this milestone, Visa had been on-network since 1997. Only a few months later, Charles Schwab and MasterCard were brought online. With Visa, MasterCard, Charles Schwab, and E*TRADE all operating on the same infrastructure, seamless global eCommerce became simultaneously available across six continents for the first time and only on our network.

Those milestones were not merely “nice customers.” They were proof points that the Internet had crossed from regional connectivity into a functional global commercial utility.

This is how, through these achievements, we enabled the globalization of eCommerce.

Provenance of Startup Servers and Early Business Development Travels

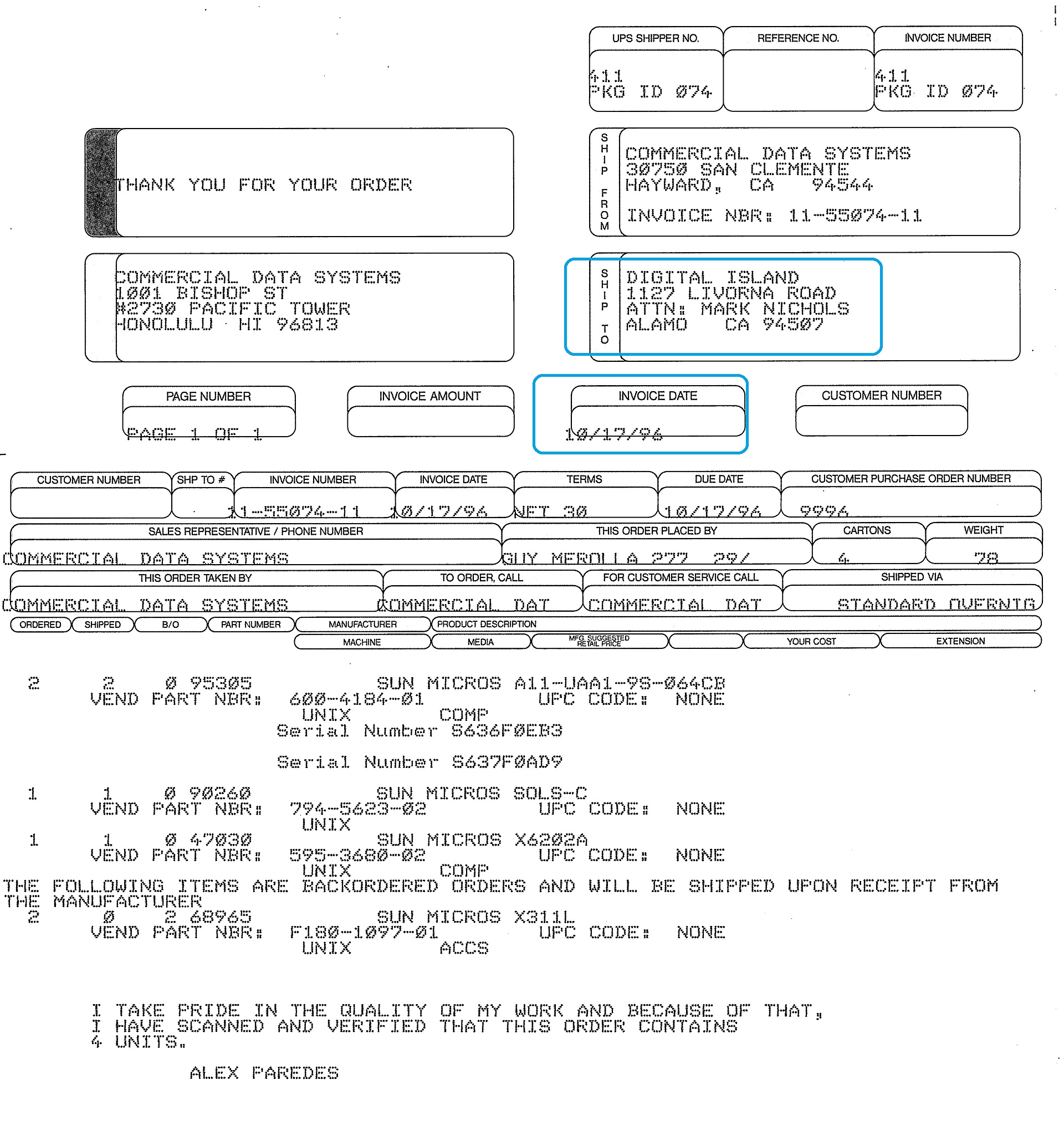

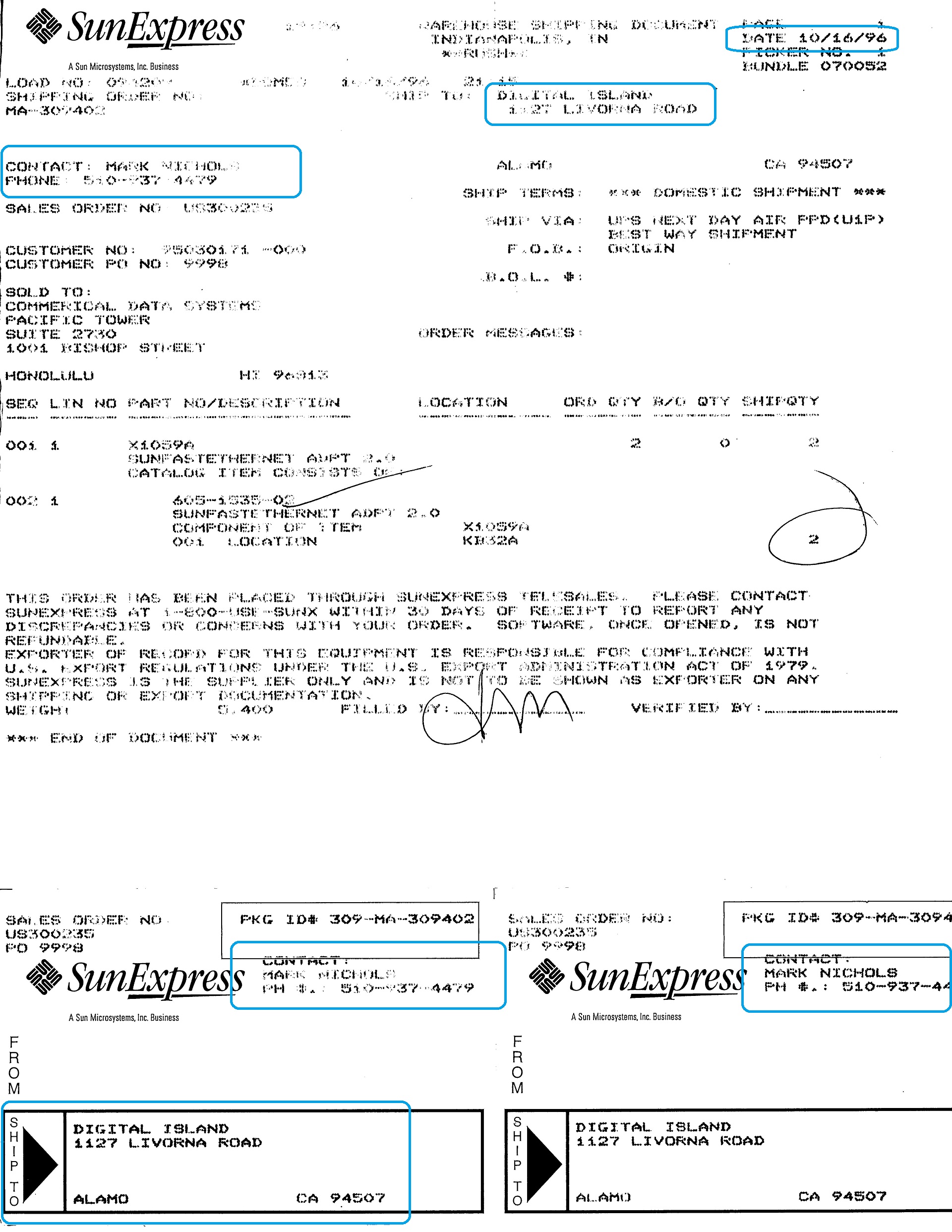

For historical context, the original servers we acquired to build the global network were shipped to my residence in Alamo, California, in 4Q 1996, because I was still working from home until we received our $3.5 million Series A investment in February 1997.

With the Series A funding in place, I contracted for 14,000 square feet of office space on San Francisco’s Embarcadero to support our first 100 employees.

____________________________

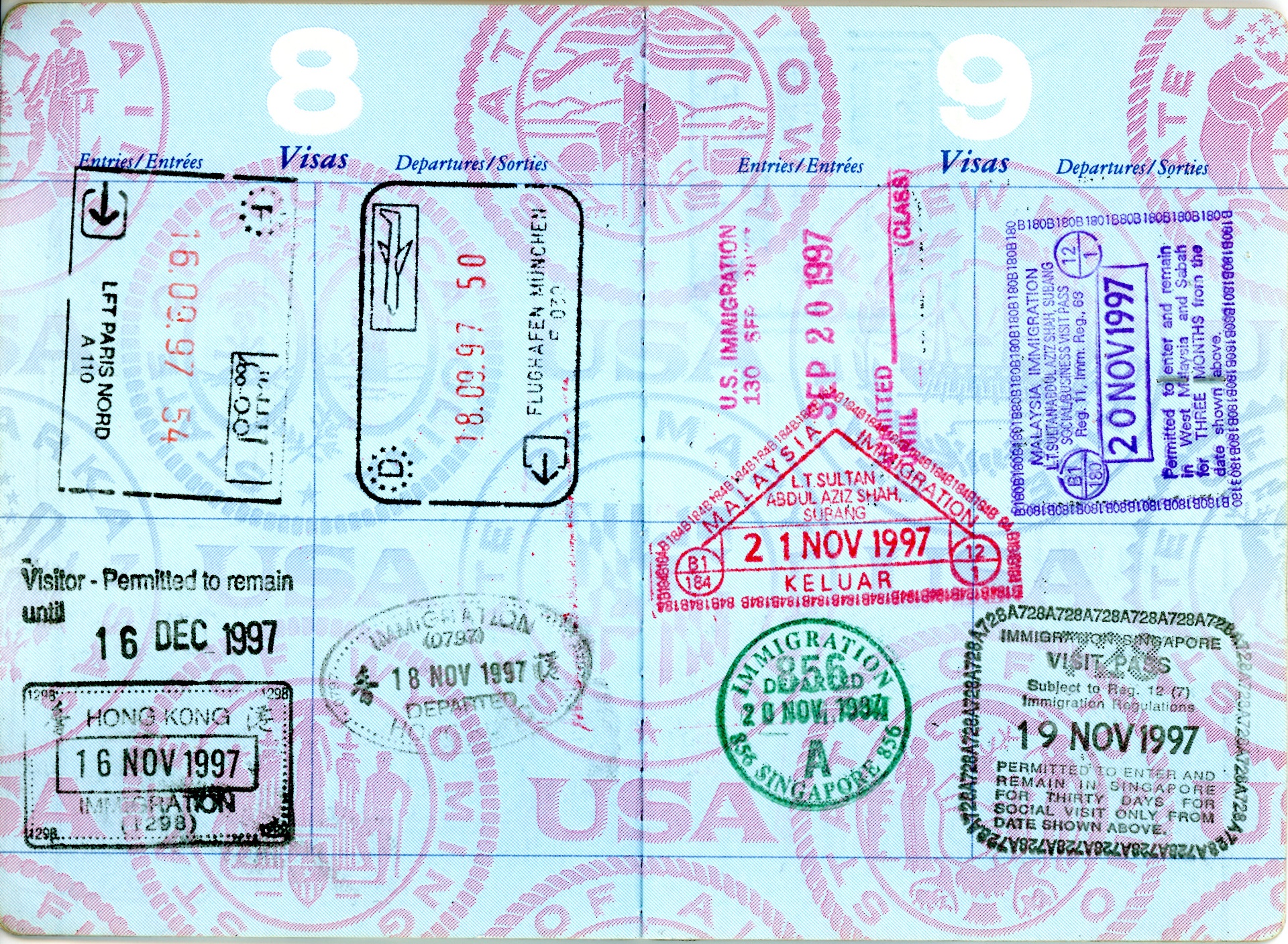

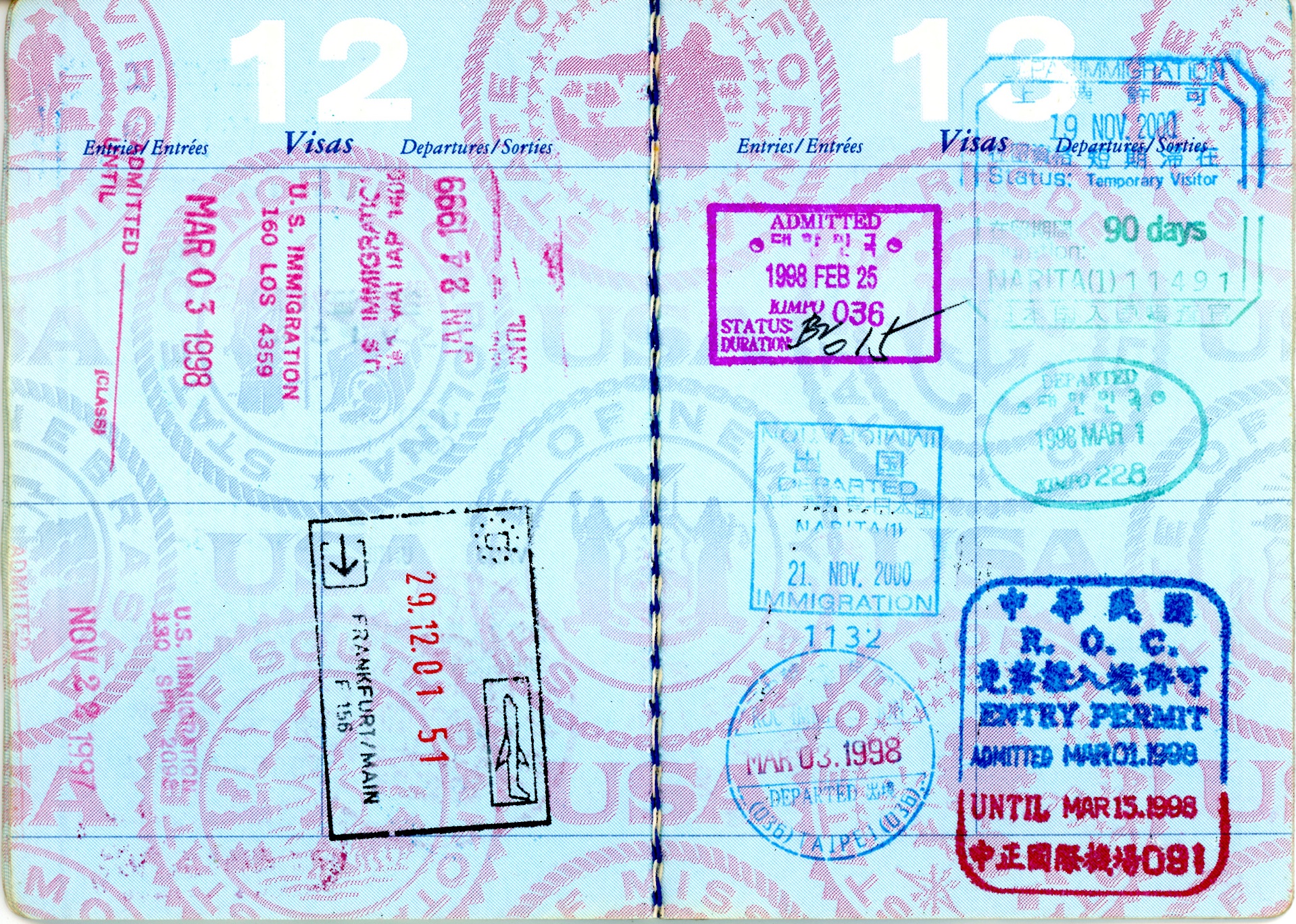

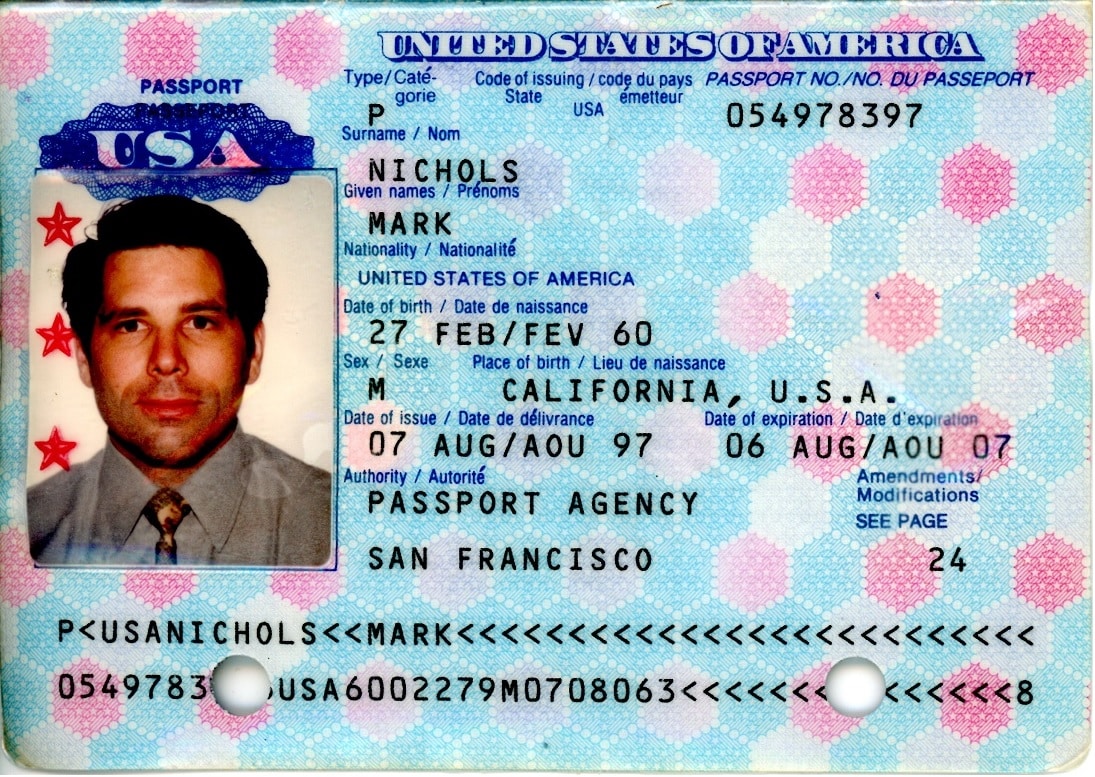

Passport stamps from my business development trips document the global efforts required to acquire the infrastructure for our network.

Internet protocols are not the physical Internet. The Web is not fiber. TCP/IP does not provision circuits.

To turn protocols and browsers into a usable worldwide system, someone had to raise serious capital, acquire real infrastructure, and operate it at global scale.

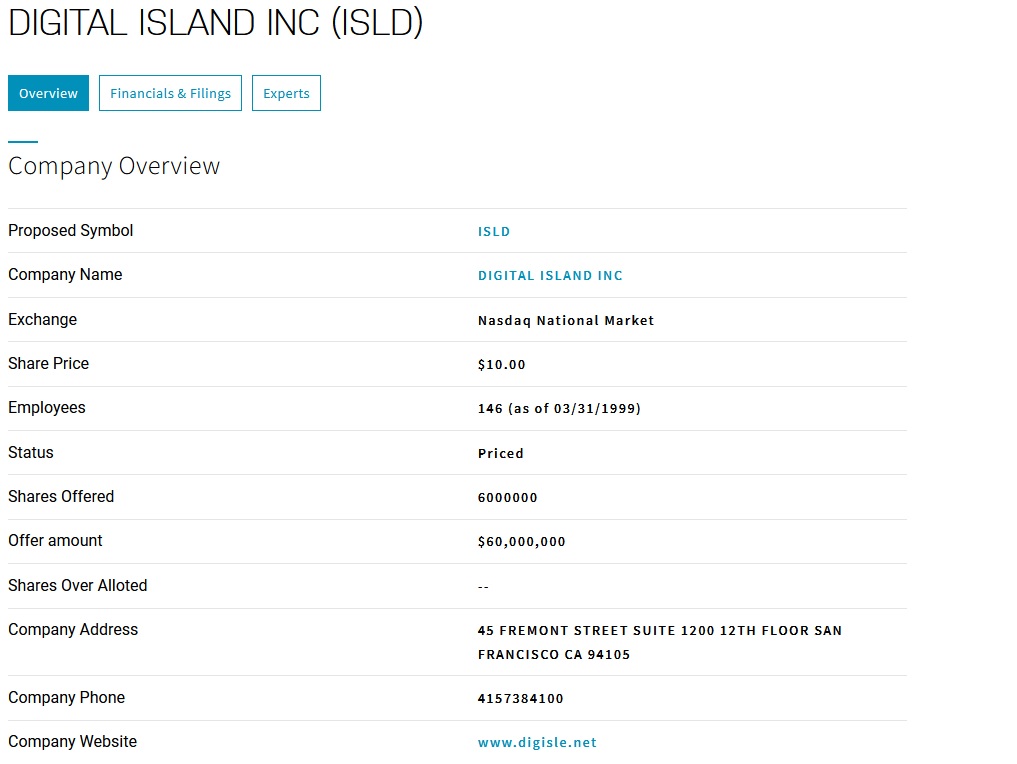

The funding record that financed the hardware, facilities, circuits, servers, and operations includes a $300K angel investment from ComVentures in November 1996, a $3.5M Series A in January 1997, a $10.5M Series B in March 1998, and a $10.5M Series C in September 1998.

A $50M Series D followed in March 1999, along with a $60M initial public offering on NASDAQ under the ticker ISLD.

Additional funding included a $45M private equity investment from Microsoft, Intel, and Compaq, and a $600M private secondary led by Goldman Sachs.

In total, we raised $779.8 million in equity, reaching a peak public valuation of $12 billion.

Total equity raised: $779.8 million

Peak public valuation: $12 billion

What It Took to Turn Internet Protocols Into a Global Utility

Internet Use Prior to Our Startup

By mid-1995, the Web was still small by any modern standard.

Contemporary counts put the number of websites in the tens of thousands, while global usage was still limited to a thin slice of humanity.

I personally owned and operated one of those early websites, PerfectWheels.com, which provided real-time market research on the limitations and potential of the Internet.

The site was image-centric, displaying product photos that were painfully slow to load over dial-up connections.

Broadband was still a distant dream, and the running joke in the industry was that using the Internet felt like trying to suck a grapefruit through a straw.

This environment sparked my Merchant Transport concept, because at the time, the standard method for using a credit card long distance was either reading the number aloud over the phone or transmitting it by fax, leaving transactions highly vulnerable to fraud.

By enabling secure, browser-based transmission over a controlled, performance-guaranteed global network, Digital Island eliminated that vulnerability at scale and made cross-border eCommerce viable for the first time.

PerfectWheels.com was later selected as a case study by Smart Valley, an association funded by Joint Venture Silicon Valley and Silicon Valley’s Institute for Regional Studies, highlighting it as an example of launching an eCommerce business using Internet and Web technology.

Fast forward to the present, and the contrast is extreme. The Web has grown from a scarce resource into a planetary utility, and the number of websites has expanded by orders of magnitude.

The Global Privateer Enabler: the Telecommunications Act of 1996

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 opened doors that had previously been closed. By reducing regulatory barriers, it allowed new entrants to negotiate circuits, interconnect with incumbent carriers, and deploy competitive services at scale. Without this legislative change, attempting to operate a global network from a U.S.-based startup would have been legally and economically infeasible.

The Act encouraged competition in long-distance and international telecommunications. It created a legal framework under which a small company could contract for international private lines, lease capacity on undersea fiber, and interconnect with major carriers without facing prohibitive regulatory restrictions. This was crucial for achieving predictable latency, reliability, and performance.

By February 1996, when President Clinton signed the Act into law, the window for first movers had opened. Within weeks, we began producing the global WAN design that would underpin Digital Island’s network. The regulatory clarity allowed us to plan a physically global network with operational guarantees, not just theoretical protocols.

Access to global circuits and interconnection points became a practical possibility. Previously, U.S. and foreign telcos restricted provisioning for new entrants. The Act changed that landscape, giving startups the legal standing to request capacity, negotiate service levels, and operate commercially in multiple countries simultaneously. Without this shift, global eCommerce could not have been enabled at the speed we achieved.

In essence, the Telecommunications Act of 1996 converted potential into action. The software protocols for TCP/IP and the Web already existed, but the operational layer necessary to support global commerce required real-world legal, financial, and contractual tools. The Act provided those tools and made the construction of a global network operationally and financially feasible.

Contact and Book Details

For speaking invitations, educational programs, institutional engagements, or related inquiries, you may call or text 1-775-600-3400, or email [email protected]. Mark is available to discuss technology infrastructure, Internet history, entrepreneurship, and global network operations.

Book Availability Click here to visit the Amazon page.

Audience and Purpose

The book was encouraged by Mark’s daughters, who suggested it could serve as a teaching tool for university-level business students. It is particularly useful for students studying technology start-ups, entrepreneurial strategy, and principles behind venture funding and IPOs.

Writing Style

The writing style is accessible to readers outside the industry, while still providing enough technical insight to keep experienced professionals informed and engaged. It balances narrative storytelling with documentary evidence of the global network build and operational challenges.

From the Epilogue:

So much unfolded so quickly, affecting countless people, reshaping cultures and economies, and producing aftereffects that continue to reverberate today. My hope is that readers appreciate the extraordinary work done by the many remarkable individuals who chose to contribute to Internet-centric telecommunications. Their efforts advanced a profoundly difficult, expensive, and unsecured endeavor with goals that, at the time, seemed nearly impossible.

The world’s commerce, trade, finance, distribution, education, human communication, and the Internet itself were all measurably different before and after the work of the Digital Island team.

I thank everyone who took part in making this possible. This outcome required people and institutions willing to accept extraordinary technical, financial, and personal risk.

“One of these days, this Internet thing is really going to catch on.”

Mark Nichols, 1994

Additional Reading

Ron’s Hawaii Ruse and Patently False Statements

In May 1996, Ron first presented a business concept initially branded Smartvision. Central to that pitch was the claim that Hawaii was a natural global Internet hub because fiber supposedly emerged from the ground there and provided direct, lower latency access to Asia.

That claim was false. Hawaii is a spur, not a gateway. It has never functioned as a control point for transpacific Internet traffic. Routing through Hawaii does not shorten paths to Asia. It lengthens them.

Within two weeks of hearing this claim, while still employed at Sprint, I asked Sprint engineering to verify the topology. Their response was unambiguous. Traffic originating in Hawaii routes east to the U.S. mainland and only then west across the Pacific on dedicated systems. There is no operational topology in which Hawaii serves as a westbound aggregation point to Asia.

Despite this, diagrams circulated to investors and the media depicted Hawaii as a bidirectional hub with westward links into Asia. Those links did not exist. The diagrams were technically infeasible and contradicted known subsea cable architecture.

From June 1996 forward, I stated internally and explicitly that Hawaii was never the value proposition. The real value was the service architecture and interconnection strategy executed from California, where carrier demarcations, peering points, and operational control actually exist.

This was not a misunderstanding that was later corrected. It was a narrative that persisted after its falsity was known. Infrastructure does not bend to storytelling. Subsea topology is governed by physics, contracts, and landing stations, not marketing claims.

Exhibit Alignment

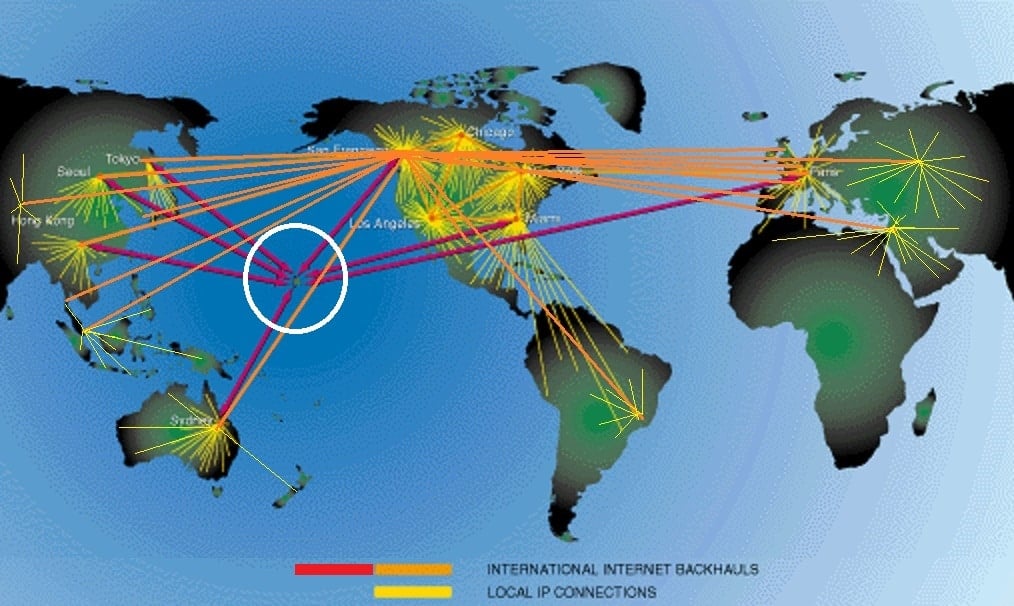

Exhibit A: Global Network Map With Hawaii Depicted as a Hub. This diagram depicts Hawaii as a bidirectional aggregation point with westward connectivity to Asia. That topology never existed. All Asia-bound traffic necessarily trombones through the U.S. mainland before crossing the Pacific.

Exhibit B: Digital Island Website Network Diagram. This diagram places the Honolulu data center at the center of international backhaul, with direct links radiating into Asia, North America, and Europe. This representation does not reflect any operational or provisionable network topology in 1996 or thereafter.

Both diagrams depict architectures that were technically infeasible at the time they were circulated. They were never corrected in the materials distributed to investors, customers, or the public.

It was not a mistake that was fixed. It was a narrative that persisted after internal correction. This repetition created a misleading perception about the role of Hawaii in the global network.

Subsea infrastructure does not bend to storytelling. The issue was never that the claim was wrong. The issue was that it was known to be wrong and repeated anyway. Customers, investors, vendors, and government agencies were exposed to a false narrative.

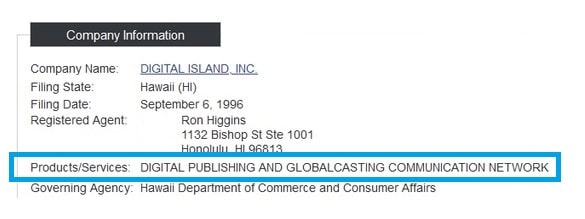

Founding Timeline, Equity Representations, and the Documentary Record

This section exists to correct discrepancies between early employment representations, later equity outcomes, and the founding narrative presented in public and regulatory filings. Contemporaneous documents, operational reality, and later SEC disclosures diverge, and the record requires clarification.

Entry Date and Operational Role. On August 5, 1996, I joined Ron and Sanne Higgins to build what became Digital Island. At that time, the company had no operating network, no executed customer contracts, and no institutional funding. The work underway involved business formation, network architecture design, customer acquisition, and infrastructure planning.

Hawaii business registration for Digital Island was filed on September 6, 1996, approximately one month after I began performing these duties.

Equity Representations at Hiring. During early employment discussions in mid-1996, prior to the execution of any venture financing or the establishment of a formal option plan, I was told I would receive approximately three percent of the company. This representation was described using an early capitalization framework of roughly 2.5 to 3.0 million shares, with my allocation described as approximately 100,000 shares.

I was also told the CEO allocation would be approximately six percent. These representations occurred before the existence of a board-governed equity plan or the controls typically associated with venture-backed companies.

These representations occurred before the existence of a board governed equity plan or the controls typically associated with venture backed companies.

Operational Milestones Preceding SEC Filings

In November 1996, I negotiated and signed the Cisco Systems services agreement. That agreement was the first executed customer contract and the instrument that made the company financeable. Venture funding followed the execution of that contract.

Throughout late 1996 and 1997, I continued performing founder-level operational functions, including network architecture decisions, customer acquisition, infrastructure contracting, and financial modeling.

SEC Capitalization Disclosure

SEC Capitalization Disclosure. On April 26, 1999, the company filed its Form S-1 registration statement. That filing reports 27,870,736 shares outstanding, as converted, as of March 31, 1999.

The S-1 reflects the following equity positions: CEO 2,075,000 shares, representing approximately 7.4 percent; CTO 195,267 shares, less than one percent; CFO 83,000 shares, less than one percent.

My equity position at that time was approximately one one-thousandth of the company, materially inconsistent with the representations made at hiring and with the scope and duration of founder-level responsibilities performed.

Founding Narrative Framing in the S 1

Within less than thirty days form when the S-1 was filed, my employment contract was terminated. At that time, the company retained 20,000 shares of my unvested equity, including unvested portions associated with my CoFounding role representations and performance-based compensation.

This sequence matters because it fixes the public record at the point of filing while foreclosing further participation in equity outcomes tied to earlier contributions.

Founding Narrative Framing in the S-1

The S-1 states that the company did not begin offering its Global IP Applications Network services until January 1997 and characterizes prior activities as unrelated to current operations.

This framing conflicts with documentary evidence of customer contracting, network design, and infrastructure work performed in 1996, including the Cisco Systems agreement executed in November 1996.

Where early operational reality is minimized in formal filings, the individuals responsible for that work are similarly minimized in the historical record.

Summary of Discrepancy

The record reflects a divergence among three elements: early employment and equity representations, founder-level operational contributions performed before and during the initial build, and equity ownership and founding attribution presented in SEC disclosures.

This section does not assert intent or motive. It documents outcomes and discrepancies based on contemporaneous documents and public filings.

The purpose is record correction.

Paper trail

[1] Employment offer letter (Aug 5, 1996): https://marknichols.com/employment-agreement-8-5-1996/

[2] Hawaii business registration filing (Sep 6, 1996): https://marknichols.com/business-registration-9-6-1996/

[3] Cisco services agreement (Nov 1996): https://marknichols.com/cisco/

[4] Digital Island Form S-1 (filed Apr 26, 1999): https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1084329/0001012870-99-001268.txt

Historical Context of the Internet & the Web

The Internet Is a Network, Not a Protocol

The Internet is a physical and operational system composed of interconnected networks. It exists only where independent networks are physically linked, operationally coordinated, and commercially sustained. Protocols operate inside that system. They do not create it.

TCP, IP, BGP, DNS, HTTP, HTML, SSL, and the World Wide Web define how data behaves once a network exists. They do not build networks, lay fiber, negotiate interconnection, guarantee performance, or enforce service levels. Confusing protocols with the Internet itself is the foundational error behind most Internet origin myths.

The Web Made Information Visible, Not Global

The World Wide Web is a software layer. Hypertext predates the Web by decades. CERN proposals in the late 1980s, early Web implementations in 1990, and browsers like Mosaic in 1993 made information easier to publish and view. None of this created global reach.

By the end of 1995, there were roughly 23,500 websites and about 16 million users worldwide. Nearly two thirds of those users were in the United States. Large portions of the world remained unreachable. A website could be standards compliant and still inaccessible to most of the planet.

The limitation was infrastructure. Performance was unpredictable. Security was minimal. Commerce at scale was impossible. Software existed. A global Internet did not.

1996: Execution Replaces Theory

By 1996, the protocols were mature and the Web was established, but the Internet still functioned as fragmented regional systems. ISPs were territorial. Telcos were monopolistic. There were no enforceable global service guarantees.

The Internet became real when the world’s networks were unified into a single operational system with defined performance, reliability, security, and accountability. This required circuits, data centers, interconnection agreements, monitoring, redundancy, and capital willing to assume global risk.

This transition did not come from academia or standards bodies. It came from execution. Protocols made global networking possible. Infrastructure made it real.

Digital Island addressed the operational gap. By delivering contractible global service behavior, the Internet became a usable commercial utility rather than a regional research experiment.

The WWW Software Layer Made Information Visual, Not Global

The World Wide Web is a software layer, not an Internet. Hypertext predates the Web by decades. Robert Cailliau proposed the CERN hypertext system in 1987. Tim Berners-Lee implemented an early version in 1990 on a NeXT workstation. Nicola Pellow made it usable beyond CERN with the Line Mode Browser. Mosaic made it visually appealing in 1993.

None of that created global reach. By the end of 1995, roughly 23,500 websites existed worldwide, with about 16 million users globally. Two-thirds of those users were in the United States. The rest of the world was effectively unreachable.

The software existed. The Internet did not. A website could be written, standards-compliant, and operational, and still be inaccessible to most of the planet. Performance was unpredictable, security was nonexistent, and commerce at scale was impossible.

The limitation was not software. It was infrastructure. Protocols describe behavior. Infrastructure determines reality. TCP/IP does not lay fiber. HTTP does not cross oceans. HTML does not negotiate peering. Browsers do not guarantee delivery.

The Internet requires physical transport, direct Tier 1 interconnection, operational control, redundancy, enforceable service levels, and capital willing to take global risk. None of that is provided by protocols or standards bodies. The Internet exists only where networks are unified into a single operational system.

Protocols Describe Behavior. Infrastructure Determines Reality.

TCP/IP does not lay fiber.

HTTP does not cross oceans.

HTML does not negotiate peering.

Browsers do not guarantee delivery.

The Internet requires:

-

Physical transport (terrestrial + submarine)

-

Direct Tier 1 interconnection

-

Operational control

-

Redundancy and disaster recovery

-

Enforceable service levels

-

Capital willing to take global risk

None of that is provided by protocols. None of it is provided by standards bodies. None of it is provided by browser authors.

The Internet exists only where networks are unified into a single operational system.

1996: When the Internet Became Real

By 1996, TCP/IP was over 20 years old, and the World Wide Web was six years old. Yet the Internet still did not exist as a global system.

Regional intranets were loosely peered, with no guarantees and no accountability. ISPs were territorial. Telcos were monopolistic. Governments restricted interconnection. No one had built a single end-to-end global network.

That changed in 1996. The Internet became real when the world’s major ISPs were interconnected into one operational system with defined performance, security, and accountability. Global reach stopped being aspirational and became contractual. Infrastructure caught up to software.

This transition did not come from academia. It did not come from protocol authors. It did not come from browser teams. It came from execution.

The Line History Keeps Getting Wrong

Protocols made the Internet possible.

Infrastructure made it real.

Calling protocol authors “fathers of the Internet” mistakes a set of protocols, which is, “A mutually agreed upon method of communication between parties,” as physical networking.

The Internet did not emerge when code was written. It emerged when someone unified the world’s networks into one operational system. That unification required agreements, circuits, data centers, staffing, operational processes, and risk-taking at global scale.

That is the line history refuses to draw. Protocol authors enabled possibility. Execution created reality. Without the physical and operational network, TCP/IP and the Web remained ideas rather than a functioning worldwide utility.

Digital Island bridged that gap. By deploying infrastructure, acquiring customers, and enforcing service levels, the Internet became contractually and commercially viable across continents. Our network delivered performance, security, and uptime guarantees previously unavailable at global scale.

Without this work, a browser could display content, but it could not reach the majority of the world. E-commerce could be designed, but transactions could not complete reliably. Financial systems, media distribution, and global communications remained fragmented and regional.

Execution also created accountability. Investors, customers, and regulators could now contract for real outcomes. The Internet became not just a research experiment, but a utility with enforceable service expectations, marking a fundamental shift in how the world could operate digitally.